Vermeer Through the Scanner: The Serene Painter Constantly Modified His Work

At first glance, Johannes Vermeer was everything but impulsive. The lab research that preceded the Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, however, shows that the artist constantly adjusted his compositions during the painting process.

Can you call to mind The Milkmaid painting? The kitchen maid – also referred to as a milkmaid – wearing her white cap, ocher bodice and blue apron, is fully focused as she pours milk from a jug into a bowl. As is usually the case with Vermeer, a window on the left of the canvas casts daylight over the tranquil scene.

The artist ensures that the background is darker on the side where the most light falls on the maid, while her shadow side on the right stands out against the pristine white part of the wall. Because of this contrast, the contours of the young woman are carved into an almost sacred space. With a little imagination, you can almost hear the flowing milk splashing gently into the bowl.

Serenity and intimacy in balanced, domestic compositions, that is the trademark of Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). The exposition at the Rijksmuseum, which brings together no less than 28 of the 37 famous Vermeers, makes this clearly evident.

And yet, the apparently steadfast composition of The Milkmaid was not predetermined: the artist had been working on the painting for quite some time when he decided to make the original scene less detailed. He painted over a few objects in the decor. Behind the kitchen maid’s head, there was once a rack with jugs. Such a rack, on which ceramic jugs were hung, was described in the estate inventory drawn up after the artist’s death. Vermeer sketched the object with black paint when he started his composition. Technological research shows that he hid it under layers of pale paint early on in the painting process.

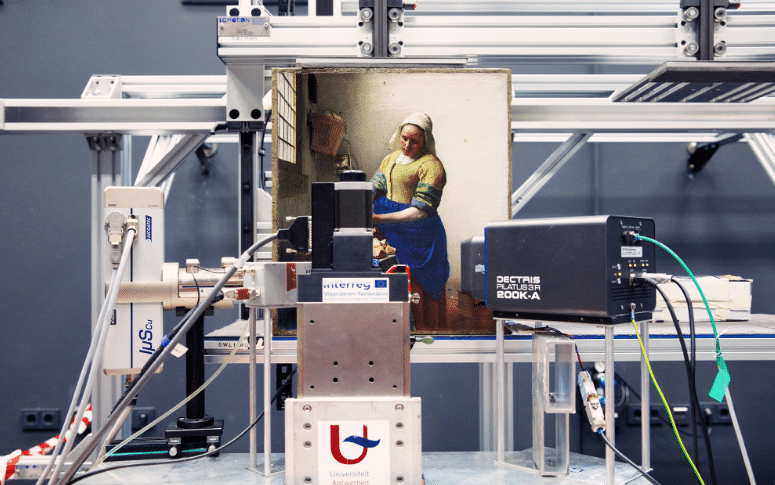

Thanks to new technological tools, partly developed by researchers at the University of Antwerp, we can look over Vermeer’s shoulder in the studio and witness how his refined, iconic compositions were created.

© University of Antwerp/Rijksmuseum

There is a second element which can no longer be seen in the final composition: on the bottom right of the scene, the dark outlines of a fire basket have been painted over. This item, used to keep newborns warm and nappies dry – no small luxury in the Vermeer family of eleven children – was also listed in the estate inventory.

The researchers subjected many other paintings, from both Dutch and foreign collections, to macroscopic scanning. This showed that Vermeer made changes to a large number of compositions during the painting process.

Removing and adding

Take The Little Street, one of Vermeer’s few outdoor paintings. Four people are pictured here: a woman sitting by the front door, engrossed in needlework; two children on their knees playing on the sidewalk; and, in the alley next to the house, a woman by a barrel. Although the characters perform different actions, everything is nicely balanced, and the canvas exudes the quiet serenity of a pleasant summer day.

During the painting process, Vermeer made a fifth person in the alley invisible In this composition, which is supposed to have Vlamingstraat. 40-42 in Delft as its subject. Perhaps he omitted the woman because doing so would add more depth to the composition. This is partly because the wastewater in the gutter now clearly flows in our direction.

There are also compositions with women and letters, which Vermeer altered during production. In the case of Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, he had first painted two chairs by the table, but he ultimately hid the chair on the right of the composition behind a green curtain which he painted over it.

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, circa 1663

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the work Mistress and Maid, the mistress is writing a letter at the table as the mistress brings her a new letter. As is often the case with seventeenth-century painters, a scene on the wall originally revealed something about the contents of the letter. But while creating the work, Vermeer changed his mind: he allowed the scene with characters on the wall to disappear almost without a trace into a dramatic, dark background.

In another scene with a letter and maid, The Love Letter, he did not reduce the original composition, but instead added a few objects. On the already painted floor tiles, Vermeer later added a cushion and a basket.

Slowly examining

Johannes Vermeer’s compositional changes were all detected by the macroscopic scanning carried out by the Rijksmuseum’s lab during the past two years. The researchers used three partially overlapping techniques and put the information together like a puzzle in order to get the best possible picture of how Vermeer worked.

The first analytical technique used to visualise the overpaintings was Reflectance Imaging Spectroscopy (RIS). Using a device, researchers illuminate the painting and then take photos. Not only do these provide information about the overpaintings, but also about the pigments used by the artist.

The second technique, Macroscopic X-Ray Fluorescence mapping (MA-XRF), also reveals underlying layers of paint and provides information about chemical substances. The technology has been around for a while, but the tool that makes it possible to microscopically examine an entire painting in a non-invasive way is not that old. It was invented a few years ago by the AXIS research group at the University of Antwerp. The tool was later commercialised by a company and is now used at the Rijksmuseum by their own research team.

For the third technique used in Amsterdam, the Macroscopic X-Ray Powder Diffraction mapping (MA-XRPD), the AXIS research team also developed a unique device. In order to scan the Vermeers using this tool, analytical chemist Frederik Vanmeert (affiliated with the University of Antwerp and the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels) went to the Rijksmuseum three times, each time for a period of a few weeks.

'A tool slowly scans the surface of the painting using a small X-ray beam'

“The tool which we invented with our team makes use of X-ray powder diffraction,” Vanmeert explains. “It slowly scans the surface of the painting using a small X-ray beam. The advantage is that you no longer have to take samples. The device glides very slowly over the sensitive top layer, taking about four days to fully scan a canvas.”

“Therefore, the scan does not visualise the underpainting, but tells us more about the painting materials used by Vermeer and how they may have degraded. In the choice of materials, you can also detect if there was an evolution in Vermeer’s oeuvre. The question is then: Is it a consistent, conscious choice or are the changes the result of a spur-of-the-moment experiment?”

Exotic painting materials

“Within the same painting, Vermeer also used varying pigments,” says Vanmeert. “An example is Vermeer’s lead white, a pigment that consists of two components. The ratio between the two components determines whether you get a bright, reflective white or a more transparent white. Vermeer usually used the latter type of lead white in the shadow zones.”

Vermeer’s ‘The Milkmaid’ (ca. 1660) is examined with, among other things, a Macro-XRPD scanner, which uses X-rays.

Vermeer’s ‘The Milkmaid’ (ca. 1660) is examined with, among other things, a Macro-XRPD scanner, which uses X-rays.© University of Antwerp/Rijksmuseum

“Another example is the costly ultramarine liberally used by Vermeer. Think of The Milkmaid’s apron, the headscarf worn by Girl with a Pearl Earring, the maidservant’s skirt in The Love Letter and the blue elements in numerous other paintings. He even used ultramarine to create shadow zones. The pigment, derived from the lapis lazuli stone from Afghanistan, was more expensive than gold back then.”

“His other painting materials were also of the best quality and came from every corner of the world. Perhaps he also wanted to increase the market value of his paintings by using expensive materials?”

In 2018, Vanmeert was also part of the international team which investigated Girl with a Pearl Earring at the Mauritshuis in The Hague. The project The Girl in the Spotlight revealed that Vermeer had painted the girl in front of a green curtain. With time, the curtain disappeared due to the discolouration of the green, transparent paint. Her eyelashes also disappeared with time.

An international team revealed that Vermeer had painted the girl in 'The Girl with a Pearl Earring' in front of a green curtain

The research showed that Vermeer very subtly played with the proportions of the components of the lead white in order to create the right optical effect. The huge pearl in her ear is an example of this illusion, demonstrated by just a couple of virtuous strokes using variants of lead white.

Even then, it was evident that Vermeer dared to alter his original composition during the painting process. He changed the position of the girl’s ear, the back of her neck and the top of the headscarf.

Prussian blue

In 1999, researchers at the restoration studio of the Mauritshuis discovered an artistic anomaly in one of Vermeer’s early paintings, Diana and her Nymphs. The sky above the Roman goddess of the hunt and the figures surrounding her was painted blue, which turned out to be Prussian blue. At the time, this was discovered using microscopic rather than macroscopic research. A sample of the paint was peeled off the painting and placed under the microscope.

The pigment studied was Prussian blue, which did not yet exist in Vermeer’s time. Because extracting the blue could potentially damage the underlying paint layer in the artwork, the Mauritshuis decided to repaint the sky in a dark-brown shade, as was done by Vermeer.

Diana and her Nymphs (approximately 1653-1654)

Diana and her Nymphs (approximately 1653-1654)© Mauritshuis

Later research showed that the woman on the right in the background initially looked straight at us. During the painting process, Vermeer changed that into an introverted gaze downwards.

Johannes Vermeer painted Diana and her Nymphs at the beginning of his career, when he still held the ambition of becoming a historical painter of large biblical and mythical scenes. But he did not get further than a few early religious paintings, even though he was a devout Catholic who maintained good contacts in Delft with his neighbours, the Jesuits.

Vanmeert scanned the relatively large canvas Diana and her Nymphs prior to the Vermeer exposition at the Rijksmuseum. But for the time being, the Antwerp researcher will not comment on his findings. For a complete report of the Johannes Vermeer scan research, we will have to wait for the symposium that is scheduled for the end of next month.

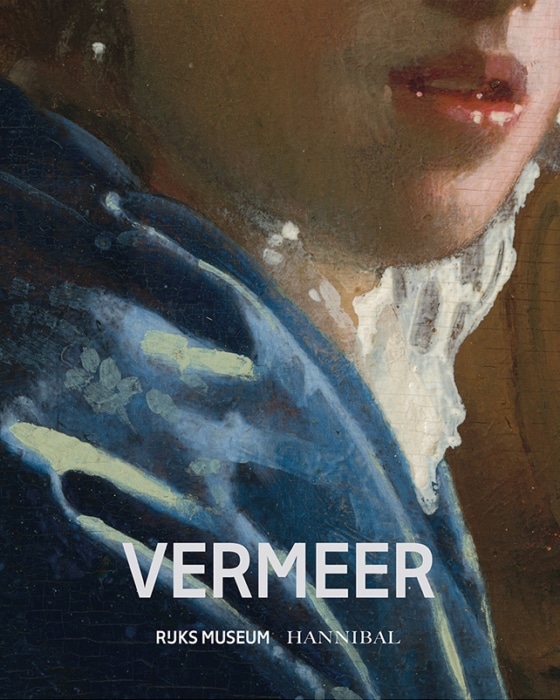

The Vermeer exhibition will be held until 4 June 2023 at the Rijksmuseum. In conjunction with the exhibition, the book Vermeer (ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor J.M. Weber) was published by Hannibal Books.